Quamina + Claude, Case 1

With 47 years of coding under my belt, and still a fascination for the new shiny, obviously I’m interested what role (if any) GenAI is going to play in the future of software. But not interested enough to actually acquire the necessary skills and try it out myself. Someday, someday. Didn’t matter; two other people went ahead without asking and applied Claude to my current code playground, Quamina. Here’s the first story. I’m going to go ahead and share it even though it will make people mad at me.

Why share? · Because our profession’s debate on this topic is simultaneously ridiculous and toxic. No meaningful dialogue seems possible between the Gas Town-and-Moltbook faction and the “AI” is a dick move camp. So, I’m not going to join in today. This is pure anecdata: What happened when Rob applied Claude to Quamina. I’m going to avoid rhetoric (in the linguistic sense, language designed to convince) and especially polemic (language designed to attack). I promise to have conclusions before too long, just not today.

What happened was… · There’s this guy Rob Sayre, I’ve known him for many years, even been in the same room once or twice, in the context of IETF work. I’ve never previously collaborated on code with him. Starting in mid-January, he’s sent a steady flow of PRs, most of which I eventually accept and merge.

The net result is that Quamina is now roughly twice as fast on several benchmarks designed to measure typical tasks.

Technical details ·

The details of what Quamina is and does are in the

README. For this discussion, let’s ignore everything

except to say that it’s a Go library and consider its two most important APIs. AddPattern() adds a Pattern (literal or

regexp) to an instance, and

MatchesForEvent considers a JSON blob and reports back which Patterns it matched. It’s really fast and the

relationship is pleasingly weak between the number of Patterns that have been added and the matching speed.

Quamina is based around finite automata (both deterministic and nondeterministic) and the rest of this technical-details section will throw around NFA and DFA jargon, sorry about that.

For code like this that is neither I/O-bound nor UI-centric, performance is really all about choosing the right

algorithms. Once you’ve done that, it’s mostly about memory management. Obviously in Quamina, the AddPattern call

needs to allocate memory to hold the finite automata. But I’d like it if the MatchesForEvent didn’t.

Go’s only built-in data structures are “map” i.e. hash table, and “slice” i.e. appendable array. (For refugees from Java, with its dozens of flavors of lists and hashes, this is initially shocking, but most Go fans come to the conclusion that Go is right and Java is wrong.) In really well-optimized code, you’d like to see all the time spent either in your own logic or in appending to slices and updating maps.

In less-well-optimized code, the profiler will show you spending horrifying amounts of time in runtime routines whose names include “malloc”, and in the garbage collector. Now, both maps and slices grow automatically as needed, which is nice, except when you’re trying to minimize allocation. It turns out that slices have a capacity, and as long as the number of things you append is less than the capacity, you won’t allocate, which is good. Thus, there are two standard tricks in the inventory of 100% of people who’ve optimized Go code:

When you make a new slice, give it enough capacity to hold everything you’re going to be adding to it. Yes, this can be hard because you’re probably using it to store input data of unpredictable size, thus…

After you’ve made a new slice, keep it around, clear it after each input record, and its capacity will naturally grow until it gets to be big enough that it fits all the rest of the records, then you’ll never allocate again.

Those PRs · Background: Quamina is equipped with what I think is a pretty good unit-test suite, and multiple benchmarks.

I started getting Rob’s PRs and initially, 100% of them were finding ways along both of those well-trodden map-and-slice paths, in places where I hadn’t noticed the opportunity. They were decent PRs, well-commented, sensible code, no loss of test coverage. After I asked to see benchmark runs to prove the gains weren’t just theoretical, they started including benchmark runs. I’ve found a few things to push back on but Rob and I had no problem sorting those out.

At the end of the day I had no qualms about merging them, but I did find myself wondering how they were built. So I asked.

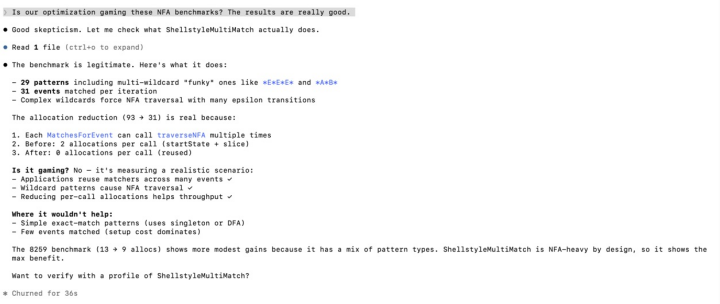

Workflow · Rob had told me right away on the first one that these were substantially Claude-generated. I asked him for his workflow and part of what he said was “I might say ‘let's do some profiles of memory and CPU on this benchmark, on main and on this branch.’ It will come up with good and bad ideas, then I pick them.”

Also: “What might be counter-intuitive is that I can context switch really quickly with it. So, you leave a comment, and I just tell Claude to fix that, because you are correct. Sometimes I go in and hand edit, but usually it gets close or perfect (what they call a "one-shot"). But I just have the conversation open, so I just pick up where we left off.”

Here’s a sample of Claude talking to Rob. You may have to enlarge it.

Not just the same-old · Then I got a surprise, because Claude and Rob spotted two pretty big improvements that aren’t on the standard list. First: To traverse an NFA, for each state you have to compute its “epsilon closure”, the set of other states you can get to transitively following epsilon transitions. I had already built a cache so that as you computed them, they got remembered. C&R pointed out “Epsilon closures are a property of the automaton structure, not the input data. Once a pattern is added and the NFA is built, the epsilon closure for any given state is fixed and never changes.” So you might as well compute it and save it when you build the NFA.

This is even better than it sounds, because (for good reasons following from Quamina’s concurrency model) my closure caches were per-thread, while the new epsilon closures were global, stored just once for all the threads. Not bad, and not trivial.

Second, when you’re computing those closures, you have to memo-ize the key functions to avoid getting caught in NFA loops.

I’d done this with a set, which in Go you implement as map[whatever]bool. R&C figured out that if you gave each

state a “closure generation” integer field and maintained a global closure-generation value, you could dodge the necessity for the

set at the cost of one integer per state. The benchmarks proved it worked.

As I wrote this piece, another PR arrived with a stimulating title: “kaizen: allocation-free on the matching path”.

Kaizen? · It’s the idea that you make things substantially better by successively introducing small improvements. We try to use the term to tag Quamina PRs that change no semantics but just make performance better or more reliable or whatever.

But GenAI is bad!?! · Yes, so they say. Go re-read that dick-move polemic.

But, I’m going to leave this little case study conclusion-free for a bit because there are two follow-up pieces. Next, the story of quamina-rs, a Claude-drive port of Quamina to Rust. Finally, Open Source and GenAI?.